Who Are We The Youth?

A Focus On Reading’s Inspiring Young Leaders

December 21, 2020

It started with a song.

A pulsing, uptempo beat with fast hits from a drum kit overlays a blaring and constant string of notes, as if an ‘80s synth was playing through a loudspeaker. Up and down, up and down, the notes arpeggiate while a siren fades in and out of the background.

Then, a single strike of the drums hits hard, and stops.

“We don’t believe you,”

The drums hit again.

“‘Cause we the people,”

The drums hit harder this time, with a pulse of the synth.

“Are still here in the rear, ayo we don’t need you,”

Silence.

“You in the killing-off-good-young-n***a mood… “

That was it- just the first 26 seconds of hip hop group A Tribe Called Quest’s 2016 track “We The People”, and junior Latoya Kibusi knew what they wanted to do. It was the summer of 2020, and as America’s latest uproar of racial injustice and police brutality against people of color raged on, the words of the song gave Kibusi an idea, and they began to formulate their own plan for action. The issues on Kibusi’s mind? Racism, racial justice, and inequality in their school, town, and country. Kibusi was already involved in RMHS’s new Reading Minority Alliance, but things weren’t going in the direction Kibusi wanted, and they knew more action needed to be taken. The high school community needed more change, more initiative, and a place for more action amongst Kibusi and their peers. Kibusi’s solution? Start their own group to make a space that would fight for change towards racial justice- but this time, no adults: no teachers, no supervisors, just Kibusi, and any of their peers that were sure to follow.

But what would they call this group? As Quest’s “We the People” played on, Kibusi knew.

Not We the People. Instead, their group’s name would be even more powerful- We the Youth.

…

It wasn’t any of the adults’ fault, but the minority alliance initiative was just not quite what RMHS needed, and Kibusi saw this plain as day.

“I and a lot of my other peers were in the Reading Minority Alliance and teachers and parents were in it, too. Students felt uncomfortable talking about trauma, and other issues for minorities in Reading, because it felt disingenuous- like no one was going to do anything anyway,” Kibusi reflected. But We the Youth would be different, and could do more by creating dialogue and a place where students didn’t have to hold back any of their thoughts or emotions.

WTY member Ava DelloRusso agreed wholeheartedly- a student-led group was the best step to better action and conversation.

“Having the teachers and adults involved is good, but you lose some of the honesty and vulnerability in discussions when you feel like you owe something to the teachers to not say the wrong things to them, and that can be hard,” she expressed. “I think we [the students] realized that we needed an area to fully be able to talk about ourselves and the issues amongst each other, so that’s the direction WTY led.”

Without the barrier of adult presence and the freedom to take whatever action Kibusi and the group’s other early leaders wanted, the new group could do so much more. Especially with leaders who are people of color themselves, facilitating discussions that are open and welcome for people of color (POC) became much easier and far more meaningful in creating real change.

Kimma Hall, one of the WTY’s original leaders, knew from the beginning that the aspect of change through outreach would be at the core of the group’s mission.

“The purpose of WTY is to create change. The group was originally formed to combat racial injustice,” she said. “However, over time we broadened our aim to promote and uplift all marginalized voices. As a group, we are focused on curating events, discussions, and collaborative safe spaces to help educate and create change.”

Since its inception in June 2020, WTY has grown to a count of about 30 members, and has already created several successful events, both in-person and online. In August, a celebration event for the art and voices of POC in the Reading community (and surrounding towns) took place on the Town Common. This event allowed the speakers and presenters to both share their experiences, but also listen to others and hear that they weren’t alone in their feelings. The vibe on the town common that day was powerful and hopeful, and with a special guest speaker it sent what Hall deemed a visible “call for action” to the town and its people.

“We had the honor of having Boston based poet Amanda Shea as our host and MC for the event,” Hall continued. “With her monologue and her spoken-word poems she was able to create an atmosphere that brought everyone in- holding space for silenced POC voices and creating a welcoming platform for young poets, activists, and artists. It was an empowering and emotional event that came together quickly and established us as a group that could accomplish anything we put our minds to.”

In a town like Reading, WTY’s dedication to finding space for minorities to be heard and understood is difficult, but undeniably necessary. As a town of 25,100 people, over 92% of Reading residents are white. The statistic is starkly reflective of RMHS’ and other Reading Public School’s demographics, a fact that is well-known by students of color, but often not a thought of white students.

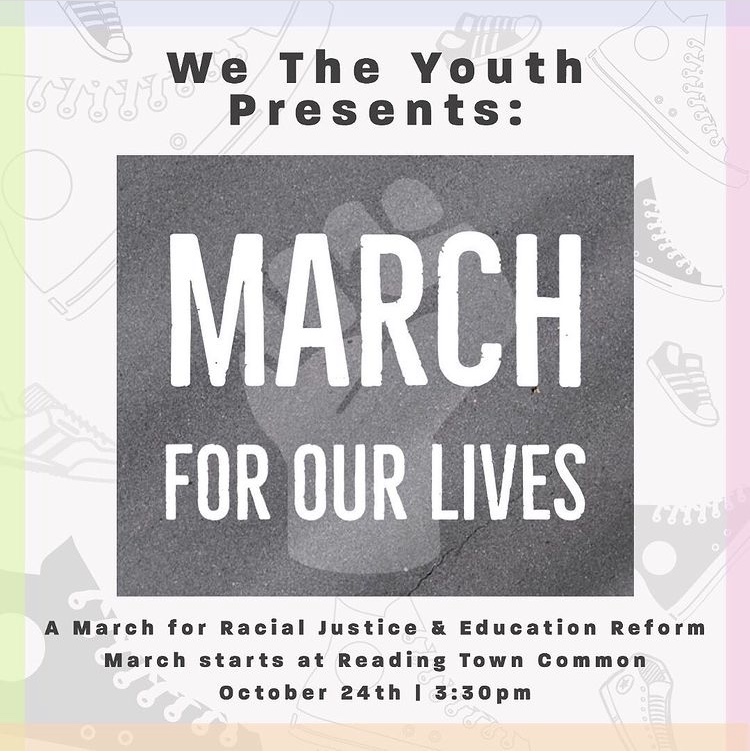

In October, riding the momentum of their August poetry event, WTY next tackled the problem of underrepresented voices of POC in the school community head on with the “March for Our Lives”. Speakers were invited once again to the Town Common, this time to talk about their experiences as POC attending RMHS, and growing up in the Reading Public Schools system. Marching from the Town Common to RMHS in a group of about 40 people, WTY demonstrated one of their most important messages to the school- movement away from systemic racism begins with making changes to the basic education of our youth.

This is a topic often discussed at WTY’s meetings. And over a few collaborative talks, WTY has already unearthed the source of this problem, finding a white-washed, one-sided curriculum to lie at its root. Over the past several months, the group has talked directly with many administrators and teachers who have chosen to attend their discussions- often from the group “RMHS Teachers Against Racism” to try and make real changes to the RMHS curriculum. Ideally, WTY sees an improved curriculum that would better reflect what people of color in the US have experienced in the past, as well as continue to experience today. While many teachers have supported the group through participating in WTY’s events and talks, their ultimate goal will be to see real and lasting change in RMHS’ education.

“It seems clear that a lack of equity and equality in the classroom curriculum has a connection to what happens in society at large. When inappropriate and racist words are allowed to be used in classroom discussions, and literature is featured that promotes a ‘white savior narrative’, those discussions can often act as desensitizers,” Hall said. “So, representation is key. When it comes to our school curriculum, we need to stop sugar-coating American history. As a community, it should be expected that we all commit to being active participants in ending racism. The March for Our Lives event was designed to bring awareness to the fact that transformation needs to begin with education both at home and especially in the public schools.”

In all, WTY has recognized and highlighted a few key aspects of a more inclusive and race-conscious education that are currently missing like gaping holes- increased representation, increased perspective, and most importantly, increased empathy.

WTY member Margaret Coles highlights the part of Reading’s education where most of the problems exist, and several RMHS classes that need more emphasis in the overall curriculum. As a group, WTY firmly believes that changes in these areas would help create a more educated and compassionate generation for the future, and is a fundamental part of their goals.

“One of the biggest problems with our humanities curriculum is that it’s so whitewashed, and that means students can’t get a realistic sense of the world and America’s history. Especially our history classes, we don’t get to learn much about history that isn’t focused on white people, both in America and around the world. Classes like Diverse Voices and Facing History and Ourselves should be required, and more accessible for students- the fact that you can only take these electives as a senior if you want to is problematic. Students shouldn’t have to seek out the full knowledge of our history, it should be a baseline of our education. If WTY can help make changes to educate people more, we’d be helping to fight against systemic racism.”

…

At the forefront of their mission, WTY sends the message that anyone- especially the young- can be an active player in facilitating change and making Reading a more tolerant place. The group also wants to combat low awareness towards systemic racism in the high school that they have encountered, a problem that can persist in a white-majority town like Reading. In turn, the low exposure to the vast extent of racism in the US means that many white students don’t know how to be effective allies towards POC, and live in what DelloRusso calls “a white bubble”. Once outside the limits of a bubble like Reading, white children who never grasped how to fight against systemic racism and listen to POC become adults with the same underdeveloped skills. Recognizing this cycle, WTY is striving to educate white students of the supportive, knowledgeable, empathetic role they can take with their POC peers to create a better future.

“Growing up in a very liberal state where we consider ourselves very accepting can be very blinding to the reality of deep-seated racism around us,” DelloRusso said. “It’s also important to be aware of microaggressions that you may trigger for people of color around you. If a POC calls you out on something you said and tells you that it is offensive to them, do not retaliate and say that you don’t think it is offensive. The answer is to listen to them- part of the respect you must give to POC is just to listen to them, and let them and their stories be heard.”

Staying vigilant and aware of microaggressions- actions or statements that inflict discrimination or harm on a person of color- is not a difficult task. WTY wants to promote this idea, and encourage RMHS students to remain conscious of racism and the unique experiences of POC by simply listening.

To give first-hand experience, Kibusi has repeatedly experienced the negative effect that white allies who don’t listen can have on young POC trying to make their opinions and experiences heard. Often, it feels like even those with the best intentions are competing to be the loudest person in the room, or the person with the most profound and powerful statement. At the same time, the people of color who are living through the very topic of the dialogue are pushed to the side.

“Change can only happen if people listen,” Kibusi said. “Teens these days are so involved with their phones and own opinions that they forget that there are actually people going through stuff around the world with actual problems. If you want to help these people, do your research and start talking to people that believe in the same thing that you do. When you build that bond with people and actively listen to the things POC have to say, you will start figuring out ways to fix the problem.”

While promoting listening, WTY also believes that students must not be afraid of participating in conversations about racial justice, no matter who they are.

“The nature of these conversations about systemic racism is that you’re learning- you’ll have questions, and you may not get it right every time, but as long as you actually listen, especially to POC, and learn what you can do, you’re taking a step in the right direction, said Coles. “I also understand the fear of participating, because I’m white, and I can only live through a perspective of sympathy and allyship. But don’t let being scared of saying the wrong thing completely deter you from not engaging in a conversation at all. If WTY can educate enough people at RMHS and beyond to adopt the mindset of antiracism and have a more informed view or what people of color are experiencing, that’s a good start.”

Like Coles says, sympathy, allyship, and acknowledgment of white privilege are fundamental to white students who want to be activists.

As a group, WTY is also striving to promote another important part of being a young activist today- consistency. Hall, Kibusi, and the other members of the group want to send a clear message that it is critical not to view activism against systemic racism and discrimination as a passing trend, but a long term battle that can eventually be won if more people are educated and conscious.

All too often, WTY sees examples of this fleeting awareness, or “performative activism”, in the RMHS community. This term refers to incidents when students and teachers make single statements or actions that are temporary and surface-level, often done as a result of peer pressure, a fear of being perceived as racist, or for social advancement. In the age of social media, it’s easy for teenagers to quickly post messages of inspiration or antiracism, or say that they ‘stand in solidarity’ with the POC community. Yet after the wave of change seems to have passed, pledges to make a difference and aid people of color in their fight seem to disappear.

“In general, I think that performative activism is essentially useless and actually contributes to maintaining the status quo. Usually, these types of one-time gestures are signs of [white] privilege more than anything else,” Hall said. “One-time performance activism seems to promote the false sense that a “one and done” statement can be an agent for change. A one-and-done approach is naïve and ineffective at best. At worst, it is a sign of callousness and insincerity acting as a “pass” that allows the status quo to continue,” she said eloquently.

Especially during the pandemic, when life and social interaction have been forced to move online, social media has sometimes become less of a tool to promote activism, and more of a space to drown out information that is actually important to the cause. Worse, posting on social media is seen as a suitable replacement to real effort and action against racism.

“Performance activism just shows how important it is to take action if you’re going to use social media to be an activist,” said Coles on the topic. “We can all say racism is bad, but if you’re not doing anything to actively combat the racism you see, you aren’t making any change. I don’t like performative activism, because I think sometimes people do it to convince themselves that they aren’t a bad person- and I know it’s hard to be engaged all the time and work towards positive change, but if you really care, there are ways to actually make it happen.”

WTY knows that change and activism aren’t easy, but the boundary between awareness and action must be crossed in order to achieve justice for people of color.

“Awareness is essential, Hall says, “But true activism is about showing up day after day. Change doesn’t happen overnight. People who are facing injustice due to racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, or discrimination based on a disability etc. face it on a day to day basis. Injustice isn’t a trend that will just go away, it is a constant illness in society. And because of that, we need to combat it with more than one dose of treatment.”

…

At the end of the day, WTY is going to do everything it takes to fight the infection of racism. Nothing the group discusses or produces is surface-level, and they work hard towards their philosophy of positive change through coupling awareness with meaningful action. The “treatments” Hall references include changes to education, creation of dialogue, or establishing safe spaces for young POC to be heard, but at their core, the group is one of progress. WTY is committed to making improvements wherever they are needed until racial justice is achieved. They aren’t a temporary fad, and they’re going to do everything it takes to meet their goals and fight systemic racism in Reading, RMHS, and beyond.

“Hopefully other RMHS students can take inspiration from the work that We The Youth has done and continues to do,” Hall reflected. “None of us in the group are experts in event planning or organizing, but we can see and say the difference between right and wrong and we will continue to take steps to side with what is right, and speak out against what is obviously wrong.”

Taking a step back, it can be hard to comprehend that We The Youth’s leaders, allies, and agents for change are only teenagers. They’re balancing school, a pandemic, and the usual struggles of adolescence while fighting a monumental battle against racism that has plagued America for centuries. Yet their work is crucial, and here’s no doubt that the world and RMHS need more of the messaging and discussions that WTY is facilitating today. For this reason the courageous work that the group is doing is beyond impressive, and imperative to the creation of a racism-free future at RMHS. Without them, it’s unlikely that the Reading community would be making any progress in this direction.

While We the Youth began with one young leader, Kibusi’s idea for a group name that started with a song has grown into a vibrant and powerful community. No matter where they’re headed, they’re going to make change towards what they know is right. They are going to be heard, not overlooked, and won’t settle for less. They are young, but powerful- and they’re leading Reading towards a brighter future.

Annemarie Cory • Dec 22, 2020 at 7:08 am

Really fantastic writing, Ally! Also, We The Youth spoke so eloquently. I am so impressed with all of you and grateful for your leadership!

Kelly Bedingfield • Dec 21, 2020 at 3:34 pm

This is a phenomenal piece, Ally. Just wow!